We can without much trouble get hold of our blobby MRI, CT, and PET scans. We rarely see the pathology slides, which are graphic.

They’re mug shots of the killers who live in those radiology blobs. And they show something else: Prostate tumors, at least early ones, are not crazed pile-ons but organized communities that look a lot like a normal prostate.

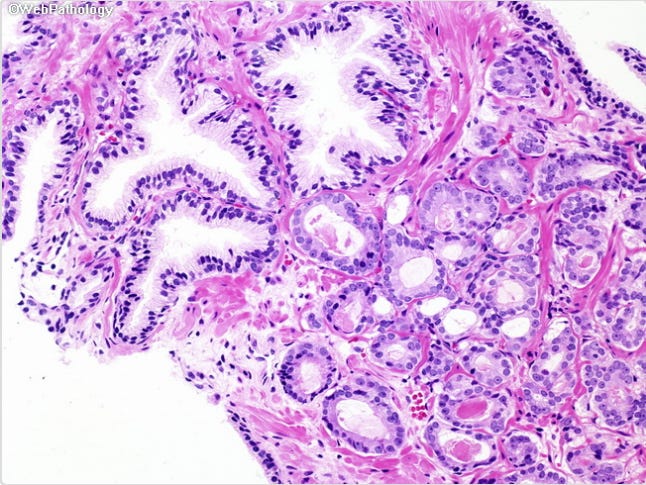

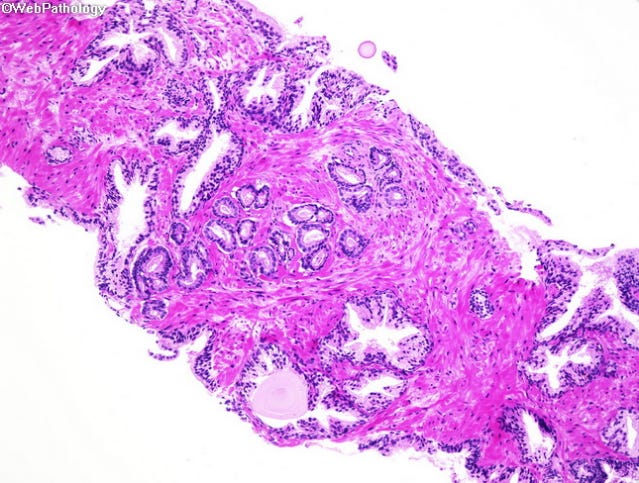

A normal prostate

Most prostate cancer begins in the glands where prostatic fluid is produced. The acinus (from the Greek for “grape”; plural acini) is the gland; the acinar cells are providing the secretions. A pathologist can tell right away that this is normal tissue:

acini are irregularly shaped

they’re separated by stroma

they’re ringed by a (not always visible) layer of basal cells

At least 90% of prostate cancers are acinar adenocarcinoma. The “acinar” you’re already looking at. You’re also looking at the “adeno” — an adenocarcinoma is carcinoma of a gland. 1

Most cancers are carcinomas, so it sometimes seems “carcinoma” is just a fancy term for cancer, but it means cancer in a specific place — the epithelial cells that make up most of the dedicated parts of organs — as opposed to, say, muscles or nerves. 2

The term for the study of cell characteristics — their shape, size, location, and so on — is histology, the cellular equivalent of anatomy. Histology can also be used (as anatomy is) to mean the cellular characteristics themselves.

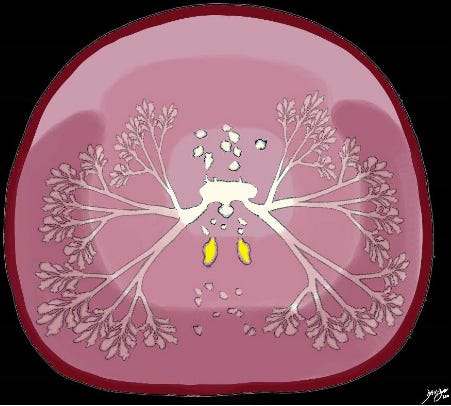

The big picture

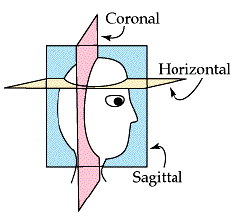

Let’s get oriented. The drawing above is a useful but slightly inaccurate cross-section of the prostate viewed top-down.3

The prostatic-fluid factory that makes up much of the prostate is a three-dimensional tree structure with acini for leaves and ducts for branches. The urethra4 is its trunk. You can see that in the image.

Unlike leaves and branches, though, ducts and acini are identical. An acinus is just where a duct ends.

Now visualize a tree sliced horizontally, the same way a pathology slide shows a sliced section of prostate. Branches will be round or oval (not tubes, the way the picture shows).

So in a pathology slide the holes of ducts and acini are identical, and a single name (pathologists chose acinus) is used for both.5

The hole is formally known as a lumen, a general term for an organ cavity.

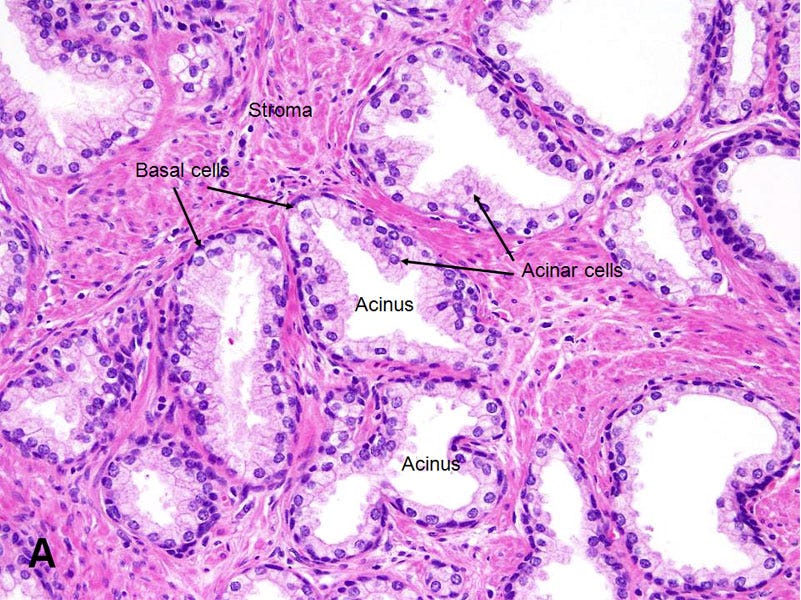

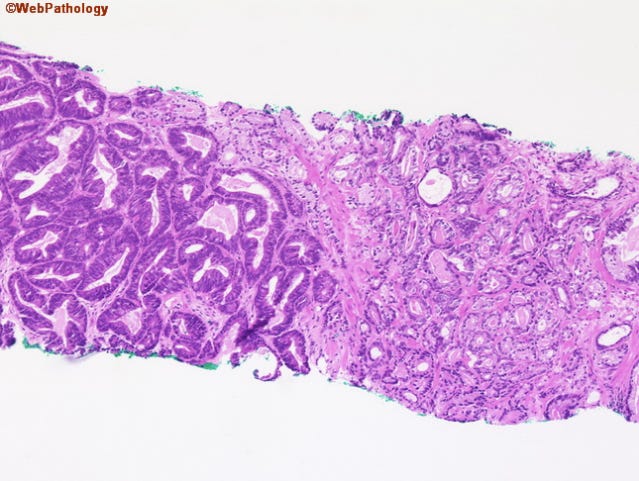

Acinar adenocarcinoma

To a pathologist, the cancer here leaps out. In contrast to the benign glands that flank it, which have large and complex lumens, the cancerous glands at the center are small, have rudimentary lumens, and show back-to-back crowding without intervening stroma.

I find this mind-blowing. We talk as if cancer were caused by a lone cell gone berserk, but here is a community of cells engaging in cancer together. It demonstrates, at least to me, that we cannot understand cancer by focusing exclusively on individual cells.6

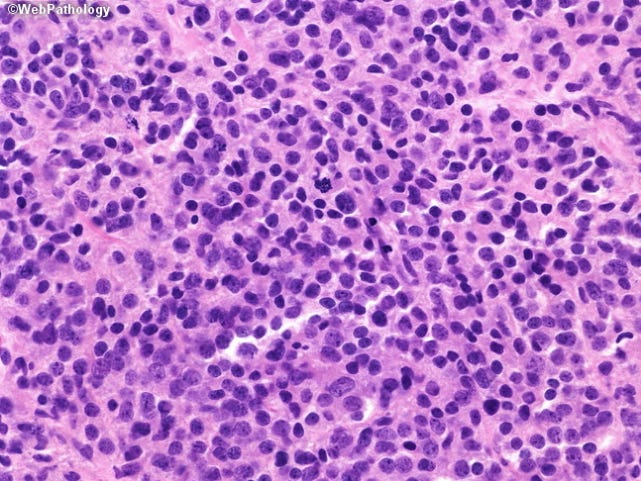

Gleason 5

In advanced cancer, glandular structure falls apart and we see the pile-on horror you expect a tumor to be.

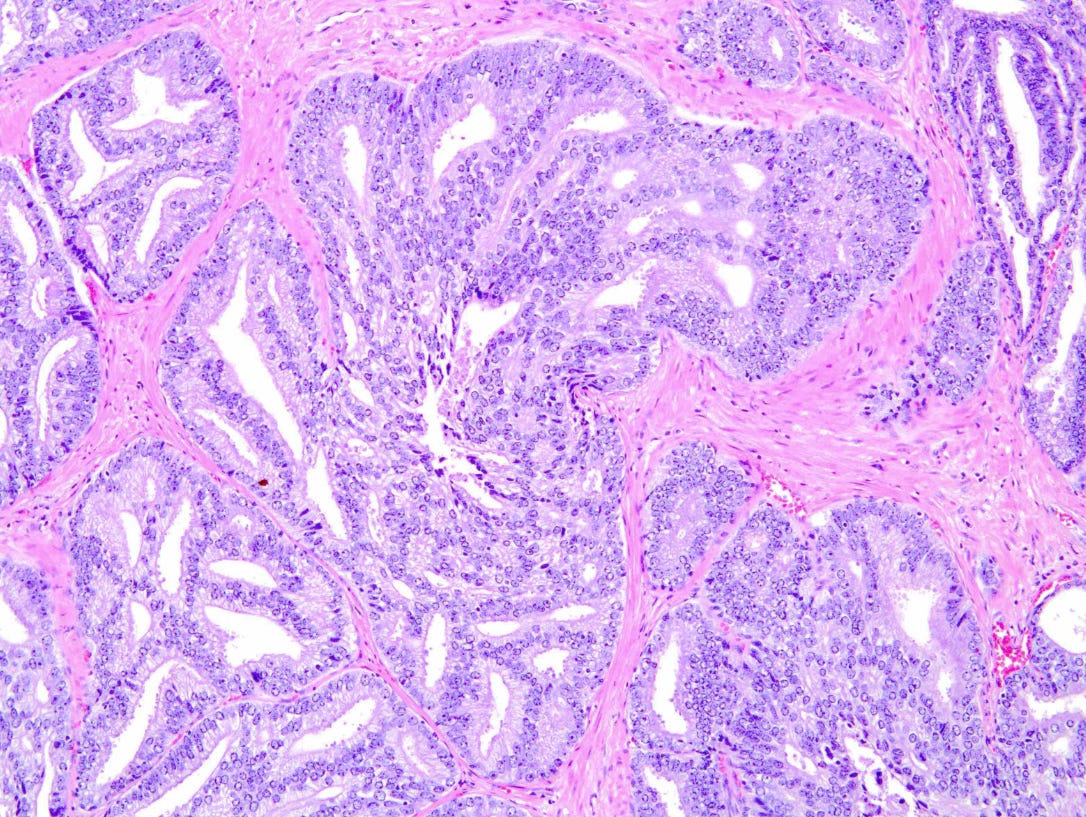

Ductal adenocarcinoma

My own cancer is ductal adenocarcinoma. It comes in several forms; all are automatically Gleason 4. This is the classic one, “papillary fronds lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelium.” You don’t have to be Jonathan Epstein7 to see it’s not acinar adenocarcinoma.

Ductal adenocarcinoma sounds confusingly similar to intraductal carcinoma, which is unrelated (though you can have both).

Intraductal carcinoma — not ductal — means cancer inside a duct. Unlike ductal, it does not carry a standard Gleason grade. Ductal is graded 4 because it was felt to have a prognosis similar to an acinar 4. But a number of grades can exhibit intraductal tumors, so it is simply reported as being present.

Pink

Your manly parts are definitely not pink but, like most cells, essentially clear. Pathologists owe their livelihood to stains that can mark out cellular structure, and the pink stain in these images — H&E, for hematoxylin and eosin — is the workhorse of pathology.8

There’s plenty more

This is a bare introduction. There are other cancer variants to talk about, including neuroendocrine. It would be good to illustrate things we see in the pathology report, like perineural invasion. We haven’t talked about cribriform or about non-ductal versions of Gleason 4. All this is for another time.

Also we’ve picked easy cases that don’t at all reflect a pathology workload. Critical treatment decisions depend on a pathologist’s ability to tell apart conditions that under the microscope look nearly identical.

Those elusive basal cells are not part of the gland; cancer here would be basal cell carcinoma.

The stroma in the photograph is considered connective tissue, not epithelial tissue, and cancer here would be a sarcoma. Prostate sarcomas are rare and have a poor prognosis.

Prostate anatomy is described in the previous post, The gland you left behind.

In a prostate, the only way you’d know you’d found a duct is if you cut at a slant and happened to cut along the length of a duct.

I’m not sure what to call this cancer collectivism, so I don’t at this point know whether other cancers exhibit it, whether it’s been explained, and whether it has a name.

A urological pathologist at Johns Hopkins who, unlike many pathologists, is famous. He pronounces it ep-stine.

The pink is the eosin. Hematoxylin is blue and is what makes the nuclei dark.