Show me the PSMA

Part 1 of a series on its who, what, when, and where

“Prostate cells express PSMA” — we hear it, we say it, but what are we talking about?

Does it coat cells like perspiration? Float out like bubbles?

How does it draw in the molecules that target it? Where do those molecules go when they arrive?

The benefits of PSMA theranostics are ours to enjoy whether we know or not. But we’d like to know.

Here we address question 1: Where is the PSMA?1

Skin in the game

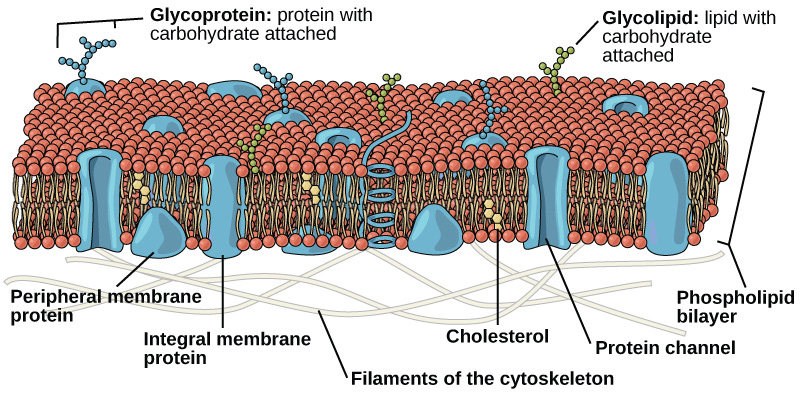

In the world of unicellular organisms it’s every cell for itself, but in multicellular organisms, cells are team players.2 There’s no cellular telepathy — to cooperate, cells have to signal each other. So cell membranes, far from being smooth balloons, resemble the antenna-studded rooftops of the VHF television era.3

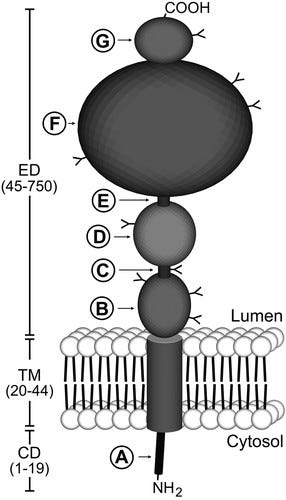

That’s not just figurative language. Here’s a sketch of a PSMA molecule:

It is rooted in the cell but dangling outside, making it a transmembrane protein. As you may already know, proteins are not just a food group but a type of molecule that appears in the body in at least 80,000 forms in dizzily varying roles; proteins make up most of what’s in a cell except for water.

The figure shows more than we need to (or are able to) discuss, but a few points will be important later. Like most proteins in a cell, PSMA is not homogeneous, the way you’d imagine a molecule to be, but instead has discernable substructures (A, B, C, and so on). Groups of these that serve a higher purpose are referred to as domains — ED stands for extracellular domain, TM for transmembrane, and CD for cytoplasmic domain. All proteins, however dissimilar, arise from an ensemble cast of only about 20 amino acids. It’s the sequences that matter, not the ingredients. PSMA is 750 amino acids long; the numbers in parenthesis show that the first 19 are inside the cell, the next 25 are in the membrane, and the remaining 706 are outside,

The figure also contains a detail you’ll see over and over. Like sentences that begin with a capital letter and end with a period, proteins have a recognized beginning (the submolecule NH₂ in the figure, more commonly called N-terminal) and end (COOH, more often C-terminal). 4

Here’s a more realistic representation of PSMA in situ:

PSMA molecules can appear as coupled pairs (a homodimer), which is what’s shown here (note the two tails). Also, the earlier figure has been crumpled. Proteins fold up in water, resulting in a messiness that turns out to be biologically crucial.

So you now know where the PSMA hangs out (literally).

You can also see why there’s no PSMA blood test. PSMA is stuck onto the cells.

The next installment will address question 2: Where does PSMA get its charm?

Bearing in mind that I’m an inquisitive patient with time to kill and not a medical professional.

Exploiting this cooperative Eden is how cancer goes rogue — a terrifying subject that will get its own blog post.

This is only one of many ways a cell can communicate with its environment. Cell membranes are so much less boring than you’d expect:

PSMA is a glycoprotein (as seen at upper left).

A Type I transmembrane protein has its N terminal outside the cell; inside is Type II. (So PSMA is Type II.) This isn’t necessarily interesting except to biochemists, but part of this blog’s aim is to get you past the lingo — you’ll feel smug rather than anxious when you see it mentioned. CD46, a promising theranostic biomarker that might surpass PSMA in several ways, is Type I. CD46 will be featured in an upcoming post.

PSMA is expressed more in advanced prostate cancer, probably because they need more folate. See https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19830782/. This leads to an interesting idea: could reducing dietary folate inhibit advanced PCa? Also, possibly, earlier stage PCa may not be as sensitive to Pluvicto or its brethren...since these cells may express less PSMA.